Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices of Medical Students at Kitwe Teaching Hospital Regarding the COVID-19 Vaccine

Tel: 978738496, Email: cmulenga790@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: On the 30th of January, 2020 the respiratory tract infecting disease caused by the novel coronavirus now called COVID-19 (i.e. the short form for Corona virus disease 2019), was declared globally a public health emergency. In this regard, medical students can be a sufficient and reliable source of information. The main aim of the study is to ascertain the “knowledge perceptions and practices of medical students at Kitwe teaching hospital regarding the COVID-19 Vaccine”. Healthcare students, most of whom in some cases are called upon to help as front-line health workers would not only need sufficient knowledge about a crisis such as the one we are facing, but also prioritization in the vaccination protocol. This research thus seeks to help in identifying possible concerns that need attention to deep awareness as well as encourage sufficient vaccination uptake from members of this group.

Objectives: This study aimed to assess the knowledge and perceptions of medical students regarding the COVID-19 vaccine at Kitwe Teaching Hospital (KTH).

Methodology: A cross-sectional survey design was employed as the study only observed what was on the ground. The sample size was calculated to be approximately 150. The study employed an online self administered questionnaire in compliance with existing public health requirements like social distancing and reduced person to person interactions. After collecting the data, entry of the data and analysis was carried out using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 26.

Results: Out of the calculated sample size of 150, a total of 141 individuals were interviewed making the response rate to be 94%. The majority were male 87 (62.1%) while only 53 (37.9%) females took part in the study. Different age groups took part and the highest frequency was recorded for the age group 21-25 years with 97 (67.8%) participants. The acceptance rate for the COVID-19 vaccine among the study participants was 58.2% with 48.9% willing to take the vaccine when their turn came. From the data analyzed, the knowledge levels were good with 73.8% of the participants having good knowledge of COVID-19 vaccination. This study also found that 55% of medical students were willing to play a role in the fight against COVID-19 if given a chance to, 16.1% were not willing and 28% were not sure.

Conclusion and recommendation: Medical students at KTH showed good knowledge levels and positive attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, with 73.8% of the participants having good knowledge and the acceptance rate of COVID-19 vaccine among the study participants being 58.2% with 48,9% willing to take the vaccine when their turn came. In addition, they were willing to play a role given the chance. Some of the students still held on to misconceptions about the vaccine with ideas most likely obtained from non-academic sources which shouldn't be the case among medical students.

Keywords

Knowledge • Perceptions • COVID-19 vaccines • Medical students • Vaccination • Zambia

Abbreviations

CDC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; HCW: Health Care Workers; KTH: Kitwe Teaching Hospital; SARS-COV-2: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; WHO: World Health Organization

Introduction

Back ground

The World Health Organization (WHO) was on 31st December of 2019 alarmed by a cluster of pneumonia patients in Wuhan City, Hubei Province of China. The cause of this pneumonia was a week later identified to be a new form of Coronavirus (novel Coronavirus-2019) and also the illness it causes was named COVID-19. COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency and pandemic on January 30, 2020, and March 11, 2020, respectively by the world health organization [1].

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacted a heavy toll on the world in terms of the burden of disease and deaths. It has also displayed catastrophic consequences to the potentiality of the global economies; insurance industry, healthcare systems to mention a few. The world has faced extraordinary challenges such as community quarantines, country lock-downs, and travel restrictions [2].

Although no cure has been found for COVID-19 and current treatment guidelines of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as well as WHO majorly focus on symptomatic management, much emphasis has been placed on prevention. Standard recommendations to prevent infection or the five golden rules of good hygiene to stop Coronavirus as some put it are: covering the mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing with a flexed elbow or into tissue that you can safely throw away, washing one's hands often with soap and water for 20 seconds at least, not touching your face with unwashed hands plus correctly wearing a mask when in public, keeping a distance of about 1.5 meters away from others and staying home if unwell as well as avoiding crowds. In addition to these golden rules is getting vaccinated.

COVID-19 vaccines are a very new medical intervention/ innovation that has been developed in the shortest time ever recorded, as many vaccines take approximately 10-15 years to reach the public. This innovation is believed to provide the best hope for a permanent solution to controlling the pandemic [3].

On April 12, 2021, Zambia received its first doses of COVID-19 intending to get 8.4 million people aged 18 and older vaccinated. As of August 6, 2021, 180,956 are fully vaccinated which is about 1.3%. Such slow progress to delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination by citizens across the country can be attributed to misinformation surrounding the subject. Myths and rumors such as the vaccine may alter one's DNA, deliver a microchip into the body, or it can make one magnetic have been quickly on social media. “Reliance on social media might have contributed to uncertainty around COVID-19, for example, about whether people have natural immunity and whether specific home remedies (garlic, vitamins, and rinsing noses with saline) help protect against coronavirus.”. The same can be said to account for the hesitancy of people toward the COVID vaccination.

Having experienced the third wave leaving COVID-associated deaths in Zambia at 3,459, according to the Zambia National Public Health Institute, people must take steps to safeguard themselves from infection of the virus and limit its spread to others. Despite not being actively involved in managing COVID-19 patients, students from medical and allied health sciences do and can serve as information providers. They can teach their community about maintaining personal hygiene, symptoms of COVID-19, and how to prevent its spread. To this effect, they are to possess a basic knowledge about the virus and be able to clear myths about the virus and the vaccine [4]. With this background, the study is aimed to assess the knowledge, perceptions, and practices regarding the COVID-19 vaccine among medical students.

Problem statement

Life following the pronouncement of the COVID-19 pandemic has never been the same, we have seen a slowdown in the global economy as well as affected thousands of people who are either sick or are being killed due to the spread of the disease [5]. Such devastating effects prompted the creation of a vaccine in record time. This creation should be regarded as a solution and an important step to winning the battle, however, there has been skepticism, and the willingness of people to get the vaccine is low.

Additionally the rise of numerous campaigns launched by antivaccinationists fueled by the new technology and short span of vaccine development on social media with fabricated, false, and sometimes misleading translations feeding the conspiracy beliefs of some people. Massages of this nature cloud the minds of people when it comes to making decisions to get the vaccine. Besides since this is a voluntary exercise, why would one willingly go for something they perceive as evil?

Justification

The study aims at finding out what students in the medical field know and how they perceive the vaccine. Information obtained will therefore help identify potential concerns to be addressed and to ensure adequate uptake among this group and enable the development of educational programs to teach skills that will equip our future health practitioners to provide vaccine recommendations by offering correct information and counsel to vaccine-hesitant persons [6].

Literature Review

The COVID-19 vaccine and how it works

The efficiency of a vaccine in reducing the risk of being infected is because it trains the immune system to identify and fight pathogens like viruses and bacteria.

Many studies about the COVID-19 vaccine focus on generating feedback on the entire or part of the spike protein that is unique to the COVID-19 causing virus. Thus, when one receives the vaccination, an immune response is activated. And should the individual be infected later, the immune system can identify the virus, and as it can and is ready to attack the virus, it protects the person from COVID-19 update 45-vaccines-developement.pdf (who. int.)

Just like many other vaccines, the COVID-19 vaccines are developed following the same legal requirements that require pharmaceutical quality, safety, and efficacy as other medicines. The vaccines’ potential side effects are first analyzed in the laboratory many on animals and later on human subjects, volunteers, in this case, COVID-19 vaccines: key facts | European medicines agency.

O’Byrne, Gavin, and McNicholas, indicate that the current and ongoing treatment procedures of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and WHO mainly concentrate on symptomatic management as well as the application of infection prevention measures. Nonetheless, other drugs such as chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, and lopinavir/ritonavir have equally been tested in clinical trials.

Since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic in March of 2020, many vaccines have been developed. For zambian authorities, the first doses of the Oxford- AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine were dispensed in April 2021, despite not having sufficient information regarding the knowledge and acceptability of the said vaccine among Zambians [7]. This research seeks to reveal these issues among medical students at the Kitwe Teaching Hospital (KTH), on the Copperbelt province of Zambia.

Owning to the fact that Healthcare Workers (HCWs) are the ones closely involved in the vaccination procedure, they have in essence been prioritized for the COVID-19 vaccine. It is thus important to assess the level of knowledge and awareness in this particular priority class. In their study, Mudenda, et al. focused on evaluating the vaccine awareness and acceptance among pharmacists due to the important advisory role they play in the lives of patients as regards the means of reducing the spread of the virus and available treatment options. The study started with pharmacy undergraduate students, they being upcoming pharmacists and future custodians of medical drugs and vaccine manufacturing. Their study focused on pinpointing the bottlenecks that may affect vaccine acceptance and uptake in Zambia in the future. This conducted study hoped to help develop an extensively applicable procedure to improve future vaccination uptake in the country.

Knowledge, perceptions, and vaccination hesitancy

According to Lucia, Kelekar, and Afonso, the perceptions of healthcare personnel on a particular subject can be influenced by their knowledge about the issue. This can affect the recognition and handling of infected persons during a pandemic. At the time of their study, the level of knowledge and related perceptions of healthcare personnel regarding COVID-19 was unclear. Thus the current pandemic was a unique opportunity to access the knowledge and perceptions of health personnel as regards the prevailing situation. The study also accessed the sources of COVID-19 information that HCW had during the crisis.

Although the morbidity and mortality due to the COVID-19 seem to be lower on the African continent as compared to higher-income countries, Zambia recorded 133,659 confirmed COVID- 19 cases as of 22 June 2021 and 1,744 deaths. The country as of the said date had administered 148,304 vaccine doses. Owning to the many concerns about uncertainties regarding the COVID-19 vaccination across different countries, it is important to assess and understand the levels of vaccination acceptance among Zambians [8]. This analysis becomes critical, especially among medical students who are playing an important role in helping to shape the perceptions of the society of medical-related issues.

Mudenda, et al. defined vaccine hesitancy as “delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite the availability of vaccination services”. They indicate that across most of Africa, much uncertainty or mistrust has been shown regarding the vaccine and vaccination process alike. This can be mainly attributed to the misinformation campaigns and conspiracies circulating on social media platforms. “For any immunization program to be successful, acceptance of the vaccine is critical and mirrors the general awareness of disease risk, vaccine attitudes and demand for vaccination within the general population” [9].

In their study that focused on Zambian pharmacy students, Mudenda, et al. found that there was a great degree of hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccines despite their knowledge about the vaccines. They therein recommend health institutions to work handin- hand with medical learning institutions like Universities and related institutions that can help alleviate vaccine hesitancy, especially with pharmacy and/or medical students as they are the very future of the healthcare workforce. This work will be of great help in shaping future interventions to address perceptions, knowledge, and hesitancy regarding vaccines, and thus reduce the future spread of COVID-19 and other viruses.

As COVID-19 is spread from person-to-person transmission via droplet, feco-oral, and direct contact and has an incubation period of 2-14 days, thus applying measures that help curb the spread of the virus is a very critical intervention. Medical personnel is the key persons that are in direct contact with patients and thus a critical point of exposure to infected cases in the healthcare system. This makes medical personnel a high-risk group in terms of exposure to infection. Before the end of January 2020, safety guidelines were published by WHO and CDC to help medical frontline workers and the general public prevent and control the spread of the pandemic [10].

The role of medical students amidst a crisis

During the current pandemic, the main trend and cornerstone internationally have been volunteerism. Nonetheless, due to the many uncertainties and different views about the role medical students can play during such pandemics, student's participation in healthcare systems has been wide-ranging across different institutions. Whereas some universities have categorically prohibited any patient contact, others still have recruited students for healthcenter- based roles as student assistants or early graduates, as frontline staff [11].

There exist a very delicate balance between the risks and potential benefits of deploying medical students in public health emergencies, whether it's accepted or not. Despite the extraordinary times, we’re in, precaution should be taken not to, for example, presume a level of preparedness among medical students beyond their institutional training. Throughout their clinical attachments, most students passively participate in their training, hiding behind classmates, taking patient histories, and observing procedures. Thus bringing these young professionals to the frontline prematurely would be undoubtedly unsafe ground [12].

International frameworks highlight that “medical students are students, not employees. They are not yet medical doctors”. Despite this, these frameworks fail to accept that medical students have a very critical role not only as learners but also as clinicians-in-training. The main role of medical students is to learn medicine, despite this, these students are medical staff who care for patients. Medical students help in interviewing patients, communicating with families, and patients, and well as assisting with many clinal procedures. They also help with care coordination and discharge planning [13].

“However, allowing medical students to serve in clinical roles may benefit patients overall. There is precedent for this kind of involvement. During the Spanish flu outbreak of 1918, medical students at the University of Pennsylvania cared for patients in the capacity of physicians. In a 1952 polio epidemic in Denmark, groups of medical students were tasked with manually ventilating patients. In the current pandemic, medical schools in the United States, Italy, and the United Kingdom are graduating medical students early on the condition that they serve as frontline clinicians” [14].

Although medical students are not directly involved in the clinical care of COVID-19 patients, they are likely to come in contact with those infected with the virus, especially as they help out with routine outpatient care. Therefore, to protect their health and the health of patients from COVID-19, there is a need for a high vaccination acceptance level among medical students [15].

In a study conducted to investigate the attitudes of medical students toward COVID-19 vaccination, Sugawara, et al., acknowledge that vaccination may only be successful when the rate of acceptance among recipients is high. The study further stated that the general public considers health care workers as an important source of information on important issues such as vaccination. For this reason, medical students with a positive attitude towards vaccines may encourage widespread vaccination.

Due to the increased risks of COVID-19, people must take steps to protect themselves from being infected and limit the spread. Though medical students and allied health sciences are not directly involved in handling COVID-19 patients, they can act as reliable information sources. The students can help sensitize communities about the COVID-19 vaccine, personal hygiene, symptoms of COVID-19, and how to prevent its spread. Thus, students must at least possess the basic knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine and be able to clear the myths about it [16]. The Zambian health care system should therefore not wait until it reaches a breaking point to invite medical students. Medical students are adept at many clinical roles. Allowing them to serve may improve patient care long before the health care system reaches a personnel crisis, and in some cases may even help prevent such crises from occurring.

Objectives

Main objective of the study: This study aims to assess the knowledge, perceptions, and practices of medical students regarding the COVID-19 vaccine at Kitwe Teaching Hospital (KTH).

Specific objectives:

• To determine what and how much medical students, know about the COVID-19 vaccine.

• To assess the perceptions, misconceptions, and uncertainties if any, of students regarding the COVID-19 vaccine

• To determine the relationship between perceptions and/or knowledge and willingness of students towards the COVID-19 vaccination.

• Based on their knowledge and perceptions, assess the willingness of medical students to play a role during a medical crisis such as the COVID-19.

Research questions

• What do medical students know about the COVID-19 vaccine?

• How much do students know concerning the COVID-19 vaccine?

• What views do medical students have regarding the COVID-19 vaccine?

• Is there a correlation between students’ perceptions and/or knowledge of the vaccine and their willingness to get vaccinated?

• How willing are medical students to play a role in the Corona Virus crisis?

Measurement

Operational definitions of key concepts and variables:

• A vaccine may be defined as an antigenic component relatively harmless that induces protective immunity against the corresponding infectious agent by training the immune system to create antibodies the same way it does when exposed to an actual disease thus making it stronger [17]. COVID 19 vaccine is a medication whose intention is to help provide active immunity against the novel Coronavirus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). As of June 2, 2021, the five COVID-19 vaccines approved by the Zambia Medicines Regulatory Authority (ZAMRA) were Sinopharm (Vero Cells), Jansen (Johnson and Johnson), AstraZeneca Covishield, AZD 1222 5 – Korean AstraZeneca, and the Pfizer Biotech. (ZAMRA approves 5 COVID-19 vaccines for use in Zambia) (2021).

• Vaccination is the process of introducing a vaccine into the body.

• Perceptions are a way of regarding, understanding or interpreting something. A mental impression or attitude of a subject.

• Knowledge information on the COVID-19 vaccine.

• Practice the act of being a recipient of the vaccine.

• Medical students those training to be medical doctors (MBChB) as well as clinical officers (clinicians) (Table 1).

Scales of measurement for the indicators

| Variable | Description | Measuring scale |

|---|---|---|

| Perception | 1. Very favourable | Ordinal |

| 2. Favourable | ||

| 3. Not favourable | ||

| 4. Highly unfavourable | ||

| 5. Unfavourable | ||

| Knowledge of the COVID | Knowledgeable/Not | Continuous |

| vaccine | knowledgeable | |

| Practice (Vaccination) | Vaccinated/Not vaccinated | Continuous |

Conceptual framework

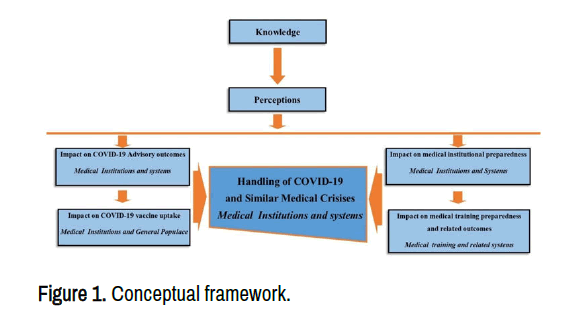

Knowledge (information) or one’s understanding of the COVID-19 vaccine is responsible for shaping their view or attitude towards the vaccine. As medical personnel may be entrusted to make vaccine recommendations to patients, their perception regarding the vaccine influences what kind of advice they give to the community and the information circulating in the entire medical system. This eventually trickles down to the people’s turn up to get vaccinated. If one views the vaccine as a poison, for instance, they are most unlikely to recommend it thus only a few people will be vaccinated.

Perceptions also give medical institutions insight on what to focus on as they train future practitioners so that their graduates will be fully prepared and equipped to handle any medical crisis or public health emergency that may arise (Figure 1).

Methodology

Study site

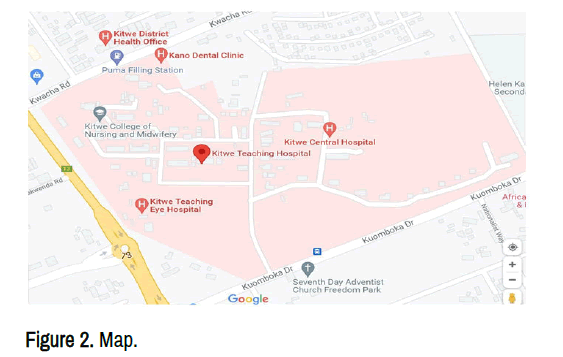

The study was conducted at Kitwe Teaching Hospital (KTH) in Copperbelt province situated southwest of Buchi and Kamitodo townships just along Kuomboka Drive in Parklands Plot number. 2831. The hospital is a third-level referral hospital serving Zambia’s second-largest populated city with daily patient traffic of 1,300 and a 664-bed capacity, (Kitwe Teaching Hospital) (Figures 2 and 3).

Target population

Students pursuing medicine at KTH from Lusaka Apex Medical University (LAMU) and those from Copperbelt University’s Michael Chilufya Sata (MCS) school of medicine. These comprised fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh-year students. Clinical medicine students from various schools in their final year (third year) doing attachments at KTH were also targeted.

Study design

A cross-sectional survey design was employed as the study only observed what was on the ground, no intervention was introduced during this study. The study design also provided a snapshot of issues to be analysed; “observations are made at one point in time so that conclusions are drawn based on observations.” and most importantly, it was easy to execute for someone as busy as a medical student (Table 2).

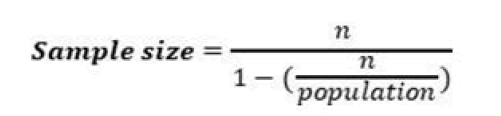

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the standard formulae shown below:

Where,

| Level of confidence (z) | 95% (1.96) |

|---|---|

| Margin of error (e) | 8% |

| Base line indicator (p) | 50% |

| Population | 800 approximately |

The sample size was calculated to be approximately 150.

Sampling procedure

Through convenience sampling, participants were selected and questionnaires were administered online. To ensure that some variability in the characteristics of respondents was maintained, common meeting places with a pool of students who had a variety of characteristics were targeted. An informed concert was sought from respondents and information obtained was kept confidential

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Medical students at KTH.

Clinical medicine students (student clinical officers) at KTH.

Exclusion criteria

Non-medical nor clinical medicine students at KTH.

Data collection

The study used a cross-sectional study approach in which the primary method of data collection involved web-based structured questionnaires. The study employed an online self-administered questionnaire to adhere to compliance with existing public health requirements like social distancing and reduced person-to-person interactions. Students were contacted via existing student social media platforms (WhatsApp and Facebook). The questionnaires were made available on Google forms during the research period. To increase and encourage participation, reminders were sent twice a week for those who did not respond within the given timeframe.

Data analysis

After collecting the data, entry of the data and analysis was carried out using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 26.

Ethical consideration

Before the study was done, permission from the hospital management was sought. Participants were adequately informed of the purpose of the study. Having obtained their consent participation in the survey was made voluntary, without any form of coercion. They were assured of maintaining anonymity and confidentiality as far as their input was concerned. Furthermore, they were assured that the study did not involve any risks to themselves or their learning situations.

Limitations

Participants may not have been truthful in answering some questions, this might not have given a true picture causing false conclusions to be drawn. Furthermore, the timing of the study ‘snap shot’ was not representative of the issue at hand. Seeing that information obtained was based on the participants’ view of the issue, it could not be generalized and the findings are open to interpretation.

Results

For this study, a total of one hundred and forty-one (141) medical students from Kitwe teaching hospital were recruited upon obtaining informed consent from them and having met the criteria for selection. Out of the calculated sample size of 150, a total of 141 individuals were interviewed making the response rate to be 94%. The sociodemographic characteristics of participants such as age and sex of the respondent were obtained, the knowledge level, attitude and practice.

Sample characteristics

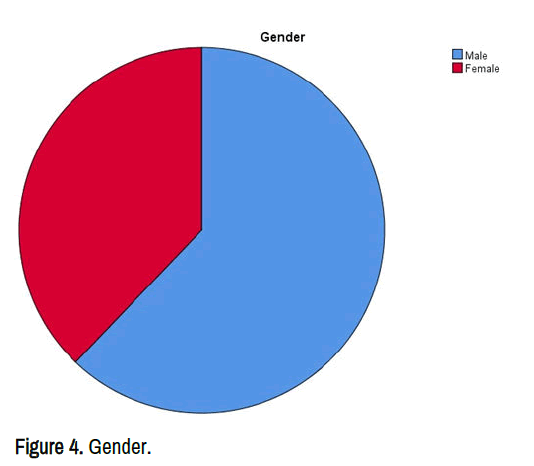

The demographic characteristics are summarized in the table below. Out of 141 participants, the majority were male 87 (62.1%) while only 53 (37.9%) females took part in the study. Different age groups took part and the highest frequency was recorded for the age group 21-25 years with 97 (67.8%) participants followed by those that were between 26-30 inclusive 44 (31.2%). The frequencies for the age group are summarized below in the bar chart. On inquiring about the programme of study revealed that 136 (97.1%) were MBChB students while 4 (2.9%) were clinical medicine students (Table 3 and Figure 4).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 21-25 | 97 | 67.8 | 68.8 |

| 26-30 | 44 | 130.8 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Gender | Male | 87 | 60.8 | 62.1 |

| Female | 53 | 37.1 | 100 | |

| Total | 140 | 97.9 | ||

| Programme of study | MBChB | 136 | 95.1 | 97.1 |

| Clinical medicine | 4 | 2.8 | 100 | |

| Total | 140 | 97.9 | ||

| System | 3 | 2.1 | ||

| Total | 143 | 100 |

Knowledge

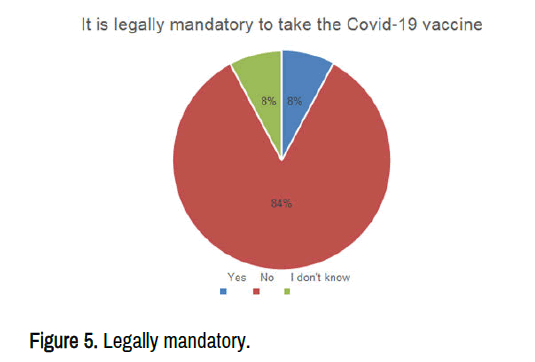

It is legally mandatory to take the COVID-19 vaccine: When asked whether it was legally mandatory to take the covid-19 vaccine, 119 (84%) responded with no while 11 (8%) said yes and another 11 (8%) said they did not know (Figure 5).

Groups of people who may or may not be eligible for taking the COVID-19 vaccine: The table below summarizes the results for the different groups: Infants (Most of the participants (85.1%) said infants were not eligible, 2.1% said they were eligible while 12.8% did not know); children and adolescents (eligible=50.4%, not eligible=42.6%, and those that didn’t know=7.1%); Above 18 (eligible=97.9%, not eligible=1.4%, and those that didn’t know=7%); Mothers (eligible=46.8, not eligible=36.9%, and those that did not know=16.3) being significant because most of the students thought that they were not eligible; Chronic conditions (eligible=75.2%, not eligible 19.9%, those that did not know=5%); Active COVID-19 (eligible=22.0%, not eligible=66.7%, those that did not know=11.3%); Those recovering (eligible=48.9%, not eligible=37.6%, and those that did not know-13.5%); Allergic to drugs or food (eligible 57.4%, not eligible=30.5, and those that did not know=12.1%); Immunocompromised (eligible=69.5%, not eligible=20.6%, and those that did not know- 9.9%) (Table 4).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | Eligible | 3 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| Not eligible | 120 | 85.1 | 87.2 | |

| Dont know | 18 | 12.8 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 | ||

| Children and adolescents | Eligible | 71 | 49.7 | 50.4 |

| Not eligible | 60 | 42 | 92.9 | |

| I don't know | 10 | 7 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Above 18 | Eligible | 138 | 96.5 | 97.9 |

| Not eligible | 2 | 1.4 | 99.3 | |

| I dont know | 1 | 0.7 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Mothers | Eligible | 66 | 46.2 | 46.8 |

| Not eligible | 52 | 36.4 | 83.7 | |

| I don’t Know | 23 | 16.1 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Chronic conditions | Eligible | 106 | 74.1 | 75.2 |

| Not eligible | 28 | 19.6 | 95 | |

| I don’t know | 7 | 4.9 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Active COVID-19 | Eligible | 31 | 21.7 | 22 |

| Not eligible | 94 | 65.7 | 88.7 | |

| I don’t know | 16 | 11.2 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Those recovering | Eligible | 69 | 48.3 | 48.9 |

| Not eligible | 53 | 37.1 | 86.5 | |

| Don’t know | 19 | 13.3 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Allergies | Eligible | 81 | 56.6 | 57.4 |

| Not eligible | 43 | 30.1 | 87.9 | |

| I don’t know | 17 | 11.9 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Immunocompromised | Eligible | 98 | 68.5 | 69.5 |

| Not eligible | 29 | 20.3 | 90.1 | |

| I don’t know | 14 | 9.8 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 |

Protective immunity against COVID-19 infection will be achieved after: On the time taken before one achieves protective immunity against COVID-19, the highest frequency was the second dose of vaccination with 48.9%, those that did not know second with 23.4%, 14 days after the first dose was third with 18.4, and finally, the first dose of vaccination had the least frequency with 9.2% (Table 5).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protective immunity against COVID-19 infection will be achieved after | The first dose of Vaccination | 13 | 9.1 | 9.2 |

| 14 days of first dose | 26 | 18.2 | 27.7 | |

| Second dose of vaccination | 69 | 48.3 | 76.6 | |

| Dont know | 33 | 23.1 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 |

Extent have the following sources of information influenced your opinion regarding vaccination: Different sources of information affected the participants differently. The factors that had a very significant effect on the participants were social media 59 (41.8%) and healthcare providers 58 (41.1%). News from TV/Radio 61 (43.3%), different agencies 58 (41.1%), and discussion 81 (57.4%) all had a somewhat significant effect on the participants. No source of information reported an insignificant effect on most of the participants (Table 6).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| News from National TV/Radio | Insignificant effect | 29 | 20.3 | 20.6 |

| Somewhat significant effect | 61 | 42.7 | 63.8 | |

| Very significant | 51 | 35.7 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Government agencies | Insignificant effect | 46 | 32.2 | 32.6 |

| Somewhat significant effect | 58 | 40.6 | 73.8 | |

| Very significant | 37 | 25.9 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Social media (Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp) | Insignificant effect | 26 | 18.2 | 18.4 |

| Somewhat significant effect | 56 | 39.2 | 58.2 | |

| Very significant effect | 59 | 41.3 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Discussions amongst friends and family | Insignificant effect | 19 | 13.3 | 13.5 |

| somewhat significant | 81 | 56.6 | 70.9 | |

| Very significant | 41 | 28.7 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Healthcare provider | Insignificant | 27 | 18.9 | 19.1 |

| Somewhat significant | 56 | 39.2 | 58.9 | |

| Very significant | 58 | 40.6 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 |

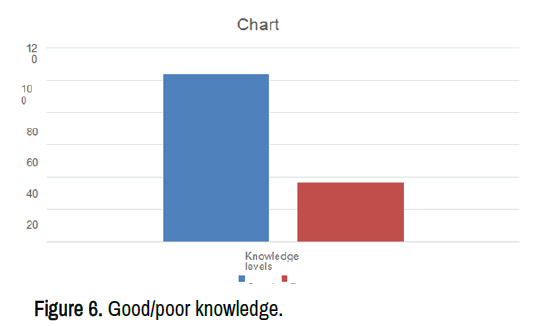

Knowledge levels: To assess knowledge about the COVID-19 vaccine, 10 questions were answered with a total score of 10. The questions ranged from basic information regarding COVID-19 vaccine methods to sources of information. This study used 10 questions, each of which was scored one point for a correct response and zero for an incorrect response. An overall knowledge score was calculated by adding up the scores for each respondent across all questions. There were (n=37, 26.2%) respondents with poor knowledge regarding the COVID-19 vaccine, while (n=104, 73.8%) had good knowledge of COVID-19 vaccination as seen in Figure 6, (Table 7).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge score | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | |

| 3 | 4 | 2.8 | 3.5 | |

| 4 | 15 | 10.6 | 14.2 | |

| 5 | 17 | 12.1 | 26.2 | |

| 6 | 17 | 12.1 | 38.3 | |

| 7 | 30 | 21.3 | 59.6 | |

| 8 | 31 | 22 | 81.6 | |

| 9 | 18 | 12.8 | 94.3 | |

| 10 | 8 | 5.7 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

The mean knowledge score for all respondents was 6.8156 out of a possible 10 points, the medium score=7.0, Standard Deviation (SD)=1.85011. Distribution of knowledge regarding. COVID-19 vaccination across all respondents is highlighted in the (Table 8).

| Valid | Mean | Std. Error of Mean | Median | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 141 | 6.8156 | 0.15581 | 7 | 1.85011 |

Descriptive statistics of likert scale questionnaire: The descriptive statistics provide general insights into medical students’ willingness toward the COVID-19 vaccine and perceptions towards the vaccine that are likely to influence their taking or abstaining from taking the vaccine. The following tables provide general insights into Medical students on perceptions of Institutional Memory (Table 9).

Students’ will

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| When my turn of vaccination comes, I am willing to take the COVID-19 vaccine. | strongly agree | 35 | 24.8 | 24.8 |

| Agree | 34 | 24.1 | 48.9 | |

| Neutral | 34 | 24.1 | 73 | |

| Disagree | 16 | 11.3 | 84.4 | |

| Strongly disagree | 22 | 15.6 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 | ||

| I will prefer to acquire immunity against COVID-19 naturally (by having the disease/subclinical infection) rather than by vaccination. | Strongly agree | 24 | 17 | 17 |

| Agree | 22 | 15.6 | 32.6 | |

| Neutral | 37 | 26.2 | 58.9 | |

| Disagree | 36 | 25.5 | 84.4 | |

| Strongly disagree | 22 | 15.6 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 | ||

| I am willing to get the COVID-19 vaccine, even if I have to pay to get it. | strongly agree | 8 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| Agree | 17 | 12.1 | 17.7 | |

| Neutral | 33 | 23.4 | 41.1 | |

| Disagree | 38 | 27 | 68.1 | |

| Strongly disagree | 45 | 31.9 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 | ||

| I will recommend my family and friends get vaccinated against COVID-19 | Strongly agree | 23 | 16.3 | 16.3 |

| Agree | 48 | 34 | 50.4 | |

| Neutral | 40 | 28.4 | 78.7 | |

| Disagree | 13 | 9.2 | 87.9 | |

| Strongly disagree | 17 | 12.1 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

According to the table above, 24.8% strongly agreed to willingly take the vaccine when their time came, 24.1% agreed and the same percentage also being neutral, 11.3% disagreed, and 15.6% strongly disagreed. However, contrasting results were seen when asked the same questions but this time including their willingness to pay for the vaccine, 31.9% strongly disagreed, 27.0% disagreed, 23.4% were neutral, only 12.1% and 5.7% agreed and strongly agreed respectively. The table also shows that most of the participants 26.2% were neutral when asked if they would prefer to acquire immunity against COVID-19 naturally (by having the disease/ subclinical infection) rather than by vaccination, 25.5% disagreed, 17.0% agreed, while those that agreed and strongly disagreed had the same percentage of 15.6%. In addition, 34.0% agreed to be willing to recommend their friends and family get vaccinated, 16.3% strongly agreed, 28.4% were neutral, 12.1% strongly disagreed and only 9.2% disagreed.

Perceptions

The tables below show the distribution of the participant’s perceptions towards certain variables. If you have taken the vaccine, certain factors must have motivated you to do so. If you are waiting for your turn to get vaccinated, then certain factors might be responsible for your decision to take the vaccine. Given below are certain statements regarding this (Table 10). Please mark your response which according to you best explains your opinion for each statement, respectively. I have taken/will take the COVID-19 vaccine because.

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I think there is no harm in taking the COVID-19 vaccine | Strongly disagree | 13 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| Disagree | 20 | 14.2 | 23.4 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 42 | 29.8 | 53.2 | |

| Agree | 42 | 29.8 | 83 | |

| Strongly agree | 24 | 17 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 10 I think there is no harm in taking the COVID-19 vaccine shows most of the participant’s 29.8% were neutral, and also agreed. Those that strongly agreed were 17%,14.2% disagreed and 9.2 strongly disagreed (Table 11).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I believe the COVID-19 vaccine will be useful in protecting me from the COVID-19 infection. | Strongly disagree | 12 | 8.5 | 8.5 |

| Disagree | 24 | 17 | 25.5 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 31 | 22 | 47.5 | |

| Agree | 52 | 36.9 | 84.4 | |

| Strongly agree | 22 | 15.6 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 11 I believe the COVID-19 vaccine will be useful in protecting me from the COVID-19 infection shows that most (36.9%) of the participant agreed, 22% were neutral, 17% disagreed, 15.6% strongly agreed, and 8.5% strongly disagreed (Table 12).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccine is available free of cost | Strongly disagree | 4 | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| Disagree | 4 | 2.8 | 5.7 | |

| neither agree nor disagree | 11 | 7.8 | 13.5 | |

| Agree | 58 | 41.1 | 54.6 | |

| Strongly agree | 64 | 45.4 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 12 COVID-19 vaccine is available free of cost shows that 45.4% strongly agreed, 41.1% agreed, 7.8% were neutral, 2.8% disagreed and 2.8% strongly disagreed (Table 13).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My health care professional has recommended me | Strongly disagree | 10 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| Disagree | 12 | 8.5 | 15.6 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 33 | 23.4 | 39 | |

| Agree | 59 | 41.8 | 80.9 | |

| Strongly agree | 27 | 19.1 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 13 My health care professional has recommended me shows that 41.8% agreed, 23.4% were neutral, 19.1% strongly agreed, 8.5 disagreed and 7.1% strongly disagreed (Table 14).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I feel the benefits of taking the vaccine outweigh the risk | Strongly Disagree | 10 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

| Disagree | 23 | 16.3 | 23.4 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 34 | 24.1 | 47.5 | |

| Agree | 50 | 35.5 | 83 | |

| Strongly Agree | 24 | 17 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 14 I feel the benefits of taking the vaccine outweigh the risk shows 35.5% agreed, 24.1% were neutral, 17% strongly agreed, 16.3% disagreed, and 7.1 % strongly disagreed (Table 15).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I believe that taking the COVID-19 vaccine is a social responsibility | Strongly disagree | 16 | 11.3 | 11.3 |

| Disagree | 16 | 11.3 | 22.7 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 32 | 22.7 | 45.4 | |

| Agree | 51 | 36.2 | 81.6 | |

| Strongly agree | 26 | 18.4 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 15 believes that taking the COVID-19 vaccine is a social responsibility show that 36.2% agreed, 22.7% were neutral, 18.4% strongly agreed, 11.3% disagreed, and 11.3% strongly disagreed (Table 16).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| There is sufficient data regarding the vaccines’ safety and efficacy released by the government | Strongly disagree | 26 | 18.4 | 18.4 |

| Disagree | 28 | 19.9 | 38.3 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 29 | 20.6 | 58.9 | |

| Agree | 34 | 24.1 | 83 | |

| Strongly agree | 24 | 17 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 16 There is sufficient data regarding the vaccines’ safety and efficacy released by the government shows that 24.1 % agreed, 20.6% were neutral, 19.9% disagreed, 18.4% strongly disagreed, and 17% strongly agreed (Table 17).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My role models/political leaders/senior doctors/scientists have taken COVID-19 vaccine. | Strongly disagree | 17 | 12.1 | 12.1 |

| Disagree | 22 | 15.6 | 27.7 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 41 | 29.1 | 56.7 | |

| Agree | 46 | 32.6 | 89.4 | |

| Strongly agree | 15 | 10.6 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 17 My role models/political leaders/senior doctors/scientists have taken COVID-19 vaccine shows that 32.6% agreed, 29.1% were neutral, 15.6% (Table 18).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Many people are taking the COVID-19 vaccine | Strongly disagree | 13 | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| Disagree | 20 | 14.2 | 23.4 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 37 | 26.2 | 49.6 | |

| Agree | 57 | 40.4 | 90.1 | |

| Strongly agree | 14 | 9.9 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 19 Many people are taking the COVID-19 vaccine shows that 40.4% agreed, 26.2% were neutral, 14.2% disagreed, 9.9% strongly agreed and 9.2% strongly disagreed.

Table 19 I think it will help eradicate COVID-19 infection shows that 31.2% agreed, 24.8% were neutral, 17.7% disagreed, 13.5% strongly disagreed, and 12.8 strongly agreed.

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I think it will help eradicate the COVID-19 infection | Strongly disagree | 19 | 13.5 | 13.5 |

| Disagree | 25 | 17.7 | 31.2 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 35 | 24.8 | 56 | |

| Agree | 44 | 31.2 | 87.2 | |

| Strongly agree | 18 | 12.8 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Influence to take the vaccine: There are still many concerns regarding the COVID-19 vaccine that may influence your decision (creating doubt in your mind) to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Give your opinion on how the following statements have influenced/will influence your decision to take the vaccine I am concerned that (Table 20).

Table 20 COVID-19 vaccine might not be available to me shows that 39.7% disagreed, 29.1 strongly disagreed, 15.6% were neutral, 7.8%, agreed, and 7.8% strongly disagreed (Table 21).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccine might not be available to me | Strongly disagree | 41 | 29.1 | 29.1 |

| Disagree | 56 | 39.7 | 68.8 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 22 | 15.6 | 84.4 | |

| Agree | 11 | 7.8 | 92.2 | |

| Strongly agree | 11 | 7.8 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 21 Might have immediate serious side effects after taking COVID-19 vaccine shows that 34.8% agreed, 19.9% were neutral, 16.3% strongly agreed, 15.6% disagreed, and 13.5% strongly disagreed (Table 22).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Might have immediate serious side effects after taking COVID-19 vaccine. | Strongly disagree | 19 | 13.5 | 13.5 |

| Disagree | 22 | 15.6 | 29.1 | |

| Neither Agree nor Disagree | 28 | 19.9 | 48.9 | |

| Agree | 49 | 34.8 | 83.7 | |

| Strongly agree | 23 | 16.3 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 22 COVID-19 vaccine may be faulty or fake shows that 36.2% were neutral, 24.1% disagreed, 21.3% agreed, 17.7% strongly agreed, and 10.6% strongly disagreed (Table 23).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccine may be faulty or fake | Strongly disagree | 15 | 10.6 | 10.6 |

| Disagree | 34 | 24.1 | 34.8 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 37 | 26.2 | 61 | |

| Agree | 30 | 21.3 | 82.3 | |

| Strongly agree | 25 | 17.7 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 23 COVID-19 vaccine was rapidly developed and approved shows that 32.6% agreed. 28.4% strongly agreed, 14.2% disagreed, 13.5% were neutral, and 11.3% strongly disagreed (Table 24).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccine was rapidly developed and approved. | Strongly disagree | 16 | 11.3 | 11.3 |

| Disagree | 20 | 14.2 | 25.5 | |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 19 | 13.5 | 39 | |

| Agree | 46 | 32.6 | 71.6 | |

| Strongly agree | 40 | 28.4 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 24 I might have some unforeseen future effects of the COVID-19 vaccine shows that 31.2% agreed, 29.8% strongly agreed, 14.2% disagreed, 12.8% were neutral, and 12.1% strongly disagreed (Table 25).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I might have some unforeseen future effects of the COVID-19 vaccine | Strongly disagree | 17 | 12.1 | 12.1 |

| Disagree | 20 | 14.2 | 26.2 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 18 | 12.8 | 39 | |

| Agree | 44 | 31.2 | 70.2 | |

| Strongly agree | 42 | 29.8 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

Table 25 COVID-19 vaccine is being promoted for commercial gains of pharmaceutical companies shows that 23.4% disagreed, 22% agreed, 21.3% were neutral, 20.6% strongly agreed, and 12.8%strongly disagreed (Tables 26,27).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccine is being promoted for commercial gains of pharmaceutical companies. | Strongly disagree | 18 | 12.8 | 12.8 |

| Disagree | 33 | 23.4 | 36.2 | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 30 | 21.3 | 57.4 | |

| Agree | 31 | 22 | 79.4 | |

| Strongly agree | 29 | 20.6 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 100 |

| Indicator | Range |

|---|---|

| Strongly disagree | 1-1.8 |

| Disagree | 1.9-2.6 |

| Neutral | 2.7-3.4 |

| Agree | 3.5-4.2 |

| Strongly agree | 4.3-5 |

| N | Mean | Indicator | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I think there is no harm in taking the COVID- 19 vaccine | 141 | 3.31 | Neutral | 1.184 |

| I believe the COVID-19 vaccine will be useful in protecting me from the COVID-19 infection. | 141 | 3.34 | Neutral | 1.182 |

| COVID-19 vaccine is available free of cost | 141 | 4.23 | Agree | 0.923 |

| My health careprofessional has recommended me | 141 | 3.57 | Agree | 1.11 |

| I feel the benefits of taking the vaccine outweigh the risk | 141 | 3.39 | Neutral | 1.157 |

| 9.6) I believe that taking the COVID-19 vaccine is a social responsibility. | 141 | 3.39 | Neutral | 1.235 |

| There is sufficient data regarding the vaccines’ safety and efficacy released by the government | 141 | 3.01 | Neutral | 1.368 |

| My role models/political leaders/senior doctors/scientists have taken COVID-19 vaccine | 141 | 3.14 | Neutral | 1.175 |

| Many people are taking the COVID-19 vaccine | 141 | 3.28 | Neutral | 1.116 |

| I think it will help eradicate the COVID- 19 infection | 141 | 3.12 | Neutral | 1.239 |

• I think there is no harm in taking the COVID-19 vaccine: The mean was 3.31 and the standard deviation was 1.184. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor disagreement with this statement.

• I believe the COVID-19 vaccine will be useful in protecting me from the COVID-19 infection: The mean was 3.34 and the standard deviation was 1.182. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor disagreement with this statement.

• COVID-19 vaccine is available free of cost: The mean was 4.23 and the standard deviation was 0.923. This means that a lot of people were in agreement with this statement.

• My health care professional has recommended me: The mean was 3.57 and the standard deviation was 1.110. This means that a lot of people were in agreement with this statement.

• I feel the benefits of taking the vaccine outweigh the risk: The mean was 3.39 and the standard deviation was 1.157. This means that a lot of people were in agreement with this statement.

• I believe that taking the COVID-19 vaccine is a social responsibility: The mean was 3.39 and the standard deviation was 1.235. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor disagreement with this statement.

• There is sufficient data regarding the vaccines safety and efficacy released by the government The mean was 3.01 and the standard deviation was 1.368. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor disagreement with this statement.

• My role models/political leaders/senior doctors/scientists have taken the COVID-19 vaccine: The mean was 3.14 and the standard deviation was 1.175. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor in disagreement with this statement.

• Many people are taking the COVID-19 vaccine: The mean was 3.28 and the standard deviation was 1.116. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor in disagreement with this statement.

• I think it will help eradicate COVID-19 infection: The mean was 3.12 and the standard deviation was 1.239. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor disagreement with this statement (Table 28).

| N | Mean | Indicator | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 vaccine might not be available to me | 141 | 2.26 | Disagree | 1.186 |

| Might have immediate serious side effects after taking the COVID-19 vaccine. | 141 | 3.25 | Neutral | 1.283 |

| COVID-19 vaccine may be faulty or fake | 141 | 3.11 | Neutral | 1.26 |

| COVID-19 vaccine was rapidly developed and approved | 141 | 3.52 | Agree | 1.339 |

| I might have some unforeseen future effects from the COVID-19 vaccine | 141 | 3.52 | Agree | 1.366 |

| COVID-19 vaccine is being promoted for commercial gains of pharmaceutical companies | 141 | 3.14 | Neutral | 1.334 |

• COVID-19 vaccine might not be available to me: The mean was 2.26 and the standard deviation was 1.186. This means that a lot of people were in disagreement with this statement.

• Might have immediate serious side effects after taking the COVID-19 vaccine: The mean was 3.25 and the standard deviation was 1.283. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor disagreement with this statement

• COVID-19 vaccine may be faulty or fake: The mean was 3.11 and the standard deviation was 1.260. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor disagreement with this statement

• COVID-19 vaccine was rapidly developed and approved: The mean was 3.52 and the standard deviation was 1.339. This means that a lot of people were in agreement with this statement.

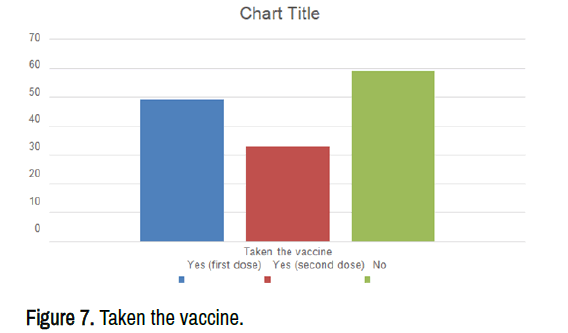

• I might have some unforeseen future effects of the COVID-19 vaccine: The mean was 3.52 and the standard deviation was 1.366. This means that a lot of people were in agreement with this statement (Figure 7).

• COVID-19 vaccine is being promoted for commercial gains of pharmaceutical companies: The mean was 3.14 and the standard deviation was 1.334. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor disagreement with this statement (Tables 29-33).

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| After getting the COVID-19 vaccine, I don’t need to follow preventive measures such as wearing a mask, sanitization, and social distancing | Strongly agree | 10 | 7 | 7.1 |

| Agree | 3 | 2.1 | 9.2 | |

| Neither Agree nor disagree | 3 | 2.1 | 11.3 | |

| Disagree | 30 | 21 | 32.6 | |

| Strongly disagree | 95 | 66.4 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 |

Willingness to play a role

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have you taken the Covid-19 vaccine? | Yes (first dose) | 49 | 34.3 | 34.8 |

| Yes (second dose) | 33 | 23.1 | 58.2 | |

| No | 59 | 41.3 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 |

| Variable | Indicators | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| If your answer to the question above is no, why not? | Not convinced | 14 | 9.8 | 25.9 |

| Haven’t found time to get it, considering to | 8 | 5.6 | 40.7 | |

| Doubts vaccine efficacy | 17 | 11.9 | 72.2 | |

| Unsure of the long term side effects | 15 | 10.5 | 100 | |

| Total | 54 | 37.8 | ||

| As a medical student, and hence future front liner, do you feel there’s something you can do to help out in the fight against COVID-19? |

Yes | 123 | 86 | 87.2 |

| No | 4 | 2.8 | 90.1 | |

| not sure | 14 | 9.8 | 100 | |

| Total | 141 | 98.6 | ||

| Given a chance would you volunteer to work in a Covid isolation ward? | Yes | 77 | 53.8 | 55 |

| No | 23 | 16.1 | 71.4 | |

| not sure | 40 | 28 | 100 | |

| Total | 140 | 97.9 |

Correlation

| Variable | Indicator | Knowledge levels | Total | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good (score above 5) | Bad (score 5 and less) | ||||

| Willingly take the vaccine | strongly agree | 28 | 7 | 35 | 0.95 |

| Agree | 24 | 10 | 34 | ||

| Neutral | 23 | 11 | 34 | ||

| Disagree | 10 | 6 | 16 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 19 | 3 | 22 | ||

| Total | 104 | 37 | 141 | ||

| Volunteer | Yes | 57 | 20 | 77 | 0.791 |

| No | 15 | 8 | 23 | ||

| not sure | 31 | 9 | 40 | ||

| Total | 103 | 37 | 140 | ||

| Taken the vaccine | Yes (first dose) | 32 | 17 | 49 | 0.148 |

| Yes (second dose) | 26 | 7 | 33 | ||

| No | 46 | 13 | 59 | ||

| Total | 104 | 37 | 141 | ||

| Can you do something | Yes | 89 | 34 | 123 | 0.291 |

| No | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| not sure | 12 | 2 | 14 | ||

| Total | 104 | 37 | 141 | ||

| Gender | Male | 62 | 25 | 87 | 0.431 |

| Female | 41 | 12 | 53 | ||

| Total | 103 | 37 | 140 | ||

| Variable | Indicator | Volunteer | Total | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yes | no | not sure | ||||

| No harm | Strongly disagree | 9 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 0.452 |

| Disagree | 8 | 6 | 6 | 20 | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 23 | 7 | 12 | 42 | ||

| Agree | 25 | 3 | 14 | 42 | ||

| Strongly agree | 12 | 5 | 7 | 24 | ||

| Total | 77 | 23 | 40 | 140 | ||

| Protection | Strongly disagree | 6 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 0.949 |

| Disagree | 13 | 5 | 6 | 24 | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 15 | 5 | 11 | 31 | ||

| Agree | 31 | 5 | 16 | 52 | ||

| Strongly agree | 12 | 5 | 5 | 22 | ||

| Total | 77 | 23 | 40 | 140 | ||

| Available for free | Strongly disagree | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.677 |

| Disagree | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||

| neither agree nor disagree | 3 | 3 | 4 | 10 | ||

| Agree | 29 | 12 | 17 | 58 | ||

| Strongly agree | 38 | 8 | 18 | 64 | ||

| Total | 77 | 23 | 40 | 140 | ||

| Recommended by healthcare provider | Strongly disagree | 7 | 2 | 0 | 9 | 0.188 |

| disagree | 8 | 0 | 4 | 12 | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 19 | 6 | 8 | 33 | ||

| Agree | 27 | 10 | 22 | 59 | ||

| Strongly agree | 16 | 5 | 6 | 27 | ||

| Total | 77 | 23 | 40 | 140 | ||

| The benefits outweigh the risk | Strongly disagree | 8 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 0.547 |

| Disagree | 14 | 3 | 6 | 23 | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 13 | 9 | 12 | 34 | ||

| Agree | 28 | 6 | 15 | 49 | ||

| Strongly agree | 14 | 4 | 6 | 24 | ||

| Total | 77 | 23 | 40 | 140 | ||

| Social responsibility | Strongly Disagree | 10 | 2 | 3 | 15 | 0.034 |

| Disagree | 10 | 3 | 3 | 16 | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 14 | 6 | 12 | 32 | ||

| Agree | 27 | 8 | 16 | 51 | ||

| Strongly Agree | 16 | 4 | 6 | 26 | ||

| Total | 77 | 23 | 40 | 140 | ||

| Efficacy | Strongly disagree | 15 | 3 | 8 | 26 | 0.601 |

| Disagree | 11 | 6 | 11 | 28 | ||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 20 | 2 | 6 | 28 | ||

| Agree | 19 | 6 | 9 | 34 | ||

| Strongly agree | 12 | 6 | 6 | 24 | ||

| Total | 77 | 23 | 40 | 140 | ||

In the previous chapter, the results of the study were presented. In this chapter, the same results are discussed regarding the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of medical students toward the COVID-19 vaccine. The study limitations are also discussed in this chapter.

Discussion

Significant research findings are interpreted and summarized in a manner conforming to the main study objective which was to assess the knowledge and perceptions of medical students regarding the COVID-19 vaccine at Kitwe Teaching Hospital (KTH).

Knowledge

Knowledge, perceptions, and practices of medical students at Kitwe Teaching Hospital towards the COVID-19 vaccine. The acceptance rate for the COVID-19 vaccine among the study participants was 58.2% with 48,9% willing to take the vaccine when their turn came. This is similar to studies in Japan, the UK, and the UAE which showed that 62.1%,64%, and 56.3% of the participants were very likely to receive a vaccine against COVID-19, respectively [18-20]. However, the rates seen in the KTH were considerably higher than 34% among personnel at Jordan University Hospital, and 26.5% among HCWs in the Democratic Republic of Congo [21,22]. Other studies though have shown higher rates of vaccine updates than seen in our study. Barello, et al., also ascertained that 86.1% of the students in Italy would take the vaccine for COVID-19, with no significant difference between acceptance among healthcare students versus non-healthcare students. Similarly, Almaki, et al., ascertained that 90.4% of the students in Saudi Arabia would be happy to be vaccinated once they became available. Lim, et al., found that only 32% of graduate students expressed vaccine hesitancy, with Riad, et al., ascertaining worldwide that only 13.9% of the dental students would reject the COVID-19 vaccine.

From the data analyzed, the knowledge levels were good with 73.8% of the participants having good knowledge of COVID-19 vaccination as seen in figure 3.3. This finding echoes some similarities to various studies undertaken in Egypt and Bangladesh indicating high knowledge of COVID-19 [23]. However, other studies have much higher knowledge rates with the vast majority (99.5%) of those surveyed in Northern Nigeria having good knowledge of COVID-19 with similarly high rates (90%) among students in Jordan with social media and the internet key information sources. I believe the numerous awareness campaigns regarding coronavirus that the university has undertaken contributed to the high scores in our study; however, further research is needed before we can say anything with certainty. Of concern though, is that 26.2% of the students surveyed had poor knowledge, which I believe came from non-scientific resources given the level of misinformation circulating regarding the vaccines. Higher rates of poor knowledge though were seen in a study in Nigeria where 96.0% of those surveyed had poor knowledge of the disease, with again social media as the main source of information [24].

Perceptions

When the participants were asked about their perceptions regarding the vaccine, most participants (61.0%) believed that it might have some unforeseen future effects. This may be because the vaccine was rapidly developed to which sixty-one of the participants agreed. Skepticism is brought about because the scientific method of research is usually a gradual one and other life-threatening conditions still do not have a vaccine up to now. Implying that the vaccine could have been fake or faulty as thirty-nine percent of our participants ascertained. Despite all these reasons, the majority (46.8%) did not seem to think the vaccine was harmful. They (52.5%), however, believed that it would be useful in protecting them against COVID-19 infection which has known no boundaries and has been ruthless to all. Such a belief is wise as it is unclear whether previous exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) provides protection against subsequent infection for those that prefer to acquire natural immunity against the infection.

Correlation between willingness and knowledge and perception

According to this study, 24.8% strongly agreed to willingly take the vaccine when their time came, 24.1% agreed and the same percentage also being neutral, 11.3% disagreed, and 15.6% strongly disagreed. There was no correlation between knowledge levels and most of the perceptions as the p-value was greater than 0.05. This finding was contrary to the findings of a survey in Vietnam that showed a significant relationship between knowledge and good practices [25]. However, there was a correlation between willingness and participants feeling like it was a social responsibility (p-value=0.048). I believe that taking the COVID-19 vaccine is a social responsibility: The mean was 3.39 and the standard deviation was 1.235 [26]. This means that a lot of people were neither in agreement nor disagreement with this statement. Despite that, a cross-tabulation showed that 43 (30.5%) that agreed that it was a social responsibility were willing to take the vaccine compared to 20 (14.2%) that disagreed but were still willing to take the vaccine [27,28].

Play a role

This study also found that 55% of medical students were willing to play a role in the fight against COVID-19 if given a chance to, 16.1% were not willing and 28% were not sure.

Conclusion

Medical students at KTH showed good knowledge levels and positive attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination, with 73.8% of the participants having good knowledge and the acceptance rate of COVID-19 vaccine among the study participants being 58.2% with 48,9% willing to take the vaccine when their turn came. Some of the students still held on to misconceptions about the vaccine with ideas most likely obtained from non-academic sources which shouldn't be the case among medical students. This study also found that 55% of medical students were willing to play a role if given a chance to, 16.1% were not willing and 28% were not sure.

Recommendations

Medical students can be very instrumental in sensitizing and encouraging the masses on the COVID-19 vaccine. For this reason, ensuring that they have correct facts about the Vaccine is very important, learning institutions should therefore deliberately incorporate topics on the disease and its prevention in their curriculum.

Furthermore, there is a need for research on the long-term side effects of the vaccine as this will help dispel any uncertainties.

Acknowledgment

I credit the completion of writing this research proposal to the Almighty God who gave me breath and the strength to work.

I would also love to extend my sincere appreciation and gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Banda, and my consultants Mr. Maphango Innocent and Mr. Mukuka Mulenga both of whom gave me the guidance and encouragement I needed during the writing process.

Special thanks to all my family and everyone for the advice and support they gave to me. I could not have done it without it

References

- Abdelhafiz AS, Mohammed Z and Ibrahim ME. Knowledge, perceptions, and attitude of Egyptians towards the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). J Community Health 45 (2020): 881–890.

- Aloweidi A, Bsisu I and Suleiman A. Hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccines: an analytical cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18 (2021): 10.

- Alzoubi H, Alnawaiseh N, Al-Mnayyis A and Lubad MA, et al. COVID-19- knowledge, attitude and practice among medical and non-medical university students in Jordan. J Pure Appl Microbiol 14 (2020): 17–24.

- Almalki MJ, Alotaibi AA and Alabdali SH. Acceptability of the COVID-19 vaccine and its determinants among university students in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines 9 (2021): 943.

- An PL, Huynh Giao, Nguyen NHT and Pham BDU, et al. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Towards COVID-19 Among Healthcare Students in Vietnam. Infect Drug Resist (2021): 3405-3413.

- Barello S, Nania T, Dellafiore F and Graffigna G, et al. ‘Vaccine hesitancy among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Epidemiol 35 (2020): 781–783.

- Bhagavathula AS, Aldhaleei AW, Rohmani J and Mahabadi AM, et al. ‘Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among health care workers: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 6 (2020): 1–9.

- Elbagoury M, Tolba MM, Nasser AH and Jabbar A, et al. The find of COVID-19 vaccine: Challenges and opportunities. J Infect Public Health 14 (2021): 389-416

- Enitan SS, Oyekale AO and Akele RY. Assessment of knowledge, perception and readiness of Nigerians to participate in the COVID-19 vaccine trial. Int J Vaccines Immun 4 (2020): 1–3.

- Gohel KH, Patel BP, Shah PM and Patel RJ, et al. ‘Knowledge and perceptions about COVID-19 among the medical and allied health science students in India: An online cross- sectional survey’. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 9 (2021 a): 104–109.

- Gohel KH, Patel BP, Shah PM and Patel RJ, et al. ‘Knowledge and perceptions about COVID-19 among the medical and allied health science students in India: An online cross- sectional survey’. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health 9 (2021 b): 104–109.

- Haleem A, Javaid M and Vaishya R. ‘Since January 2020 Elsevier has created a COVID-19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID- 19. The COVID-19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company’s public news and information. Curr Med Res Pract 10 (2020): 78–79.

- Hodgson HS, Munsatta K, Mallet G and Harris V, et al. What defines an efficacious COVID-19 vaccine? A review of the challenges assessing the clinical efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Lancent Infect Dis 12 (2021): 26-35.

- Islam MS, Siddique AB and Akter R. Knowledge attitudes and perceptions towards COVID- 19 vaccinations: a cross-sectional community survey in Bangladesh. MedRxiv 21( 2021): 1851

- Kelekar AK, Lucia CA, Afonso MN and Mascarenhas KA, et al. ‘COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy among dental and medical students’. J Am Dent Assoc 152 (2021): 596–603.

- Kerr JR, Freeman ALJ, Marteau TM, and van der Linden S, et al. Effect of Information about COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness and Side Effects on Behavioural Intentions: Two Online Experiments. Vaccines 9 (2021): 379.

- Lim LJ, Lim AJW, Fong KK and Lee CG, et al. Sentiments regarding COVID-19 vaccination among graduate students in Singapore. Vaccines 9 (2021): 1141.

- Lucia VC, Kelekar AK and Afonso NM. ‘COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students’. J Public Health (Oxf) 43 (2021): 445-449

- Mannan KA and Farhana KM. ‘Knowledge, Attitude and Acceptance of a COVID- 19 Vaccine: A Global Cross-Sectional Study’. Int Res J Bus Soc Sci 6 (2020): 23.

- Miller DG, Pierson L and Doernberg S. ‘The Role of Medical Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic’. Ann Intern Med 173 (2020): 145–146.

- Mudenda S, Mukosha M, Mayer CJ and Fadre J, et al. ‘Awareness and Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccines among Pharmacy Students in Zambia : The Implications for Addressing Vaccine Hesitancy’. Research Square (2021): 1–22.

- Nzaji MK, Ngombe LK and Mwamba GN. Acceptability of vaccination against COVID-19 among healthcare workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pragmat Obs Res 11(2020): 103-109.

- Byrne OL, Gavin B and McNicholas F. ‘Medical students and COVID-19: The need for pandemic preparedness’. J Med Ethics 46 (2020): 623-626.

- Reuben RC, Danladi MM, Saleh DA and Ejembi PE, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: an epidemiological survey in North-Central Nigeria. J Community Health 7(2020) : 1–4.

- Riad A, Abdulqader H and Morgado M. Global prevalence and drivers of dental students’ COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccines 9 (2021): 566.

- Sherman SM, Smith LE and Sim J. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross- sectional survey. Hum Vaccin Immunother 25 (2020): 1–10.

- Simoneaux R and Shafer SL. ‘Update on COVID-19 Vaccine Development’. ASA Monitor 84 (2020): 17–18.

[Crossref]

- Sugawara N, Yasui-Furukori N, Fukushima A and Shimoda K. Attitudes of Medical Students toward COVID-19 Vaccination: Who Is Willing to Receive a Third Dose of the Vaccine? Vaccines 9 (2021): 1295.

Author Info

Department of Public Health, Copperbelt University, Kitwe, ZambiaReceived: 11-May-2022, Manuscript No. IJPHS-22-63972; Editor assigned: 16-May-2022, Pre QC No. IJPHS-22-63972(PQ); Reviewed: 31-May-2022, QC No. IJPHS-22-63972; Revised: 11-Jul-2022, Rev Manuscript No. IJPHS-22-63972(R); Published: 19-Jul-2022, DOI: DOI: 10.37421/2736-6189.2022.7.284

Citation: Chanda, Mulenga A. "Knowledge, Perceptions, and Practices of Medical Students at Kitwe Teaching Hospital Regarding the COVID-19 Vaccine." Int J Pub Health Safety 7 (2022): 284.

Copyright: © 2022 Chanda MA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the creative commons attribution license which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.