Mini Review - (2020) Volume 5, Issue 1

Received: 09-Jun-2020

Published:

30-Jun-2020

, DOI: 10.37421/cgj.2020.5.124

Citation: Johnson DA. "Dietary Interventions for GI Disorders: Stepping Beyond FODMAPs". Clin Gastroenterology J 5 (2020) doi: 10.37421/Clin Gastro J.2020.5.124

Copyright: © 2020 Johnson DA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use,distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The burden of a suboptimal diet is a preventable risk for non-communicable diseases, including most gastrointestinal (GI) illnesses. Clinicians providing gastrointestinal directed care are well aware of the values of specific diets e.g., gluten free for celiac, fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols (FODMAP) for irritable bowel disease, and six food exclusion diet for eosinophilic esophagitis. There is increasing evidence that dietary intervention for maintenance of GI health and/or treatment directed intervention for disease, warrants priotization by clinicians.

Diet • Intestinal microbiome • Inflammasomes • Mediterranean diet • Immunity • Dysbiosis • High fructose corn syrup

Dietary intake is a key factor maintaining a normal gut microbiome. A high-fat, high-sugar diet affects bacterial dysbiosis [1], with a related compromise in gut integrity and immunity [2]. With fiber deprivation, alternative use of carbon sources have a direct mucosal effect depleting intestinal mucus layer, disruption of the barrier and associated bacterial translocation [3]. Changing from a plant-based Mediterranean type (https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/mediterranean-diet/art-20047801) to an animal-based diet, causes bacterial taxonomic changes resulting in alteration in bile acids metabolism, in particular sulfides,which play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Dietary fibers (fruits/vegetables) provide a vital substrate for production of butyrate and other short-chain fatty acids that enhance the immune response [4]. Butyrate affects both defensins (protect against immune response) and cathelicidins (protect against pathogenic, enteric infections), as well as down regulates transcription cytokines expressed in IBD [5] and promote differentiation of T-regulatory (Treg) lymphocytes thereby decreasing immune activation. Conversely, low-fiber diets increase intestinal permeability facilitating the problem of translocation [6].

Diets high in fat and starch basically have the same effect as lowfiber diets [4]. Increases in tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interferon and intestinal permeability are noted, with a decrease in MUC2 (coats intestinal epithelium/protects against partcles/infectious surface agents translocating to the inner mucous layer). Both Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) involve this translocation [7]. A high-fat diet alone decreases colonic Tregs and promotes cologenic bacteria [4].

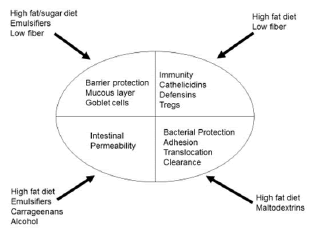

The “standard” Western diet (WD) provides considerable exposure to diet emulsifiers and food additives, which are nearly universal in processed foods but can have harmful effects, in particular on intestinal barrier function and immunity (Figure 1). Carboxymethyl cellulose and polysorbate-80 are routinely used in baked goods and ice cream to enhance palletization. Conversely these additives thin the mucus layer, increase gut permeability, increase translocation affect biomic changes associated with inflammation [8]. Maltodextrin is another additive used as a thickener and sweetener, but also can thin the intestinal mucus layer, increase gut permeability impair intracellular bacteria and promote bacterial biofilm [9]. Carrageenan is also frequently used to increase texture (particularly in dairy products and sauces), but also increases intestinal permeability, facilitating bacterial/antigenic translocation [10].

Figure 1: Potential adverse intestinal impacts of diet components (modified from reference 4).

Intake of a WD has been shown to induce a proliferative immune response and associated systemic inflammation particularly through inflammasome activation which promote inflammation and immune response in a protective way for the host, mitigating defensive response to pathogens, antigens, metabolic or cellular stress or neoplasia [11]. Overreaction of inflammatory and immune responses (via proinflammatory cytokines) however, serves as an important pathogenic factor in a wide array of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases including cardiovascular disease, obesity, diabetes, IBD and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Among all kinds of inflammasomes, the NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domaincontaining 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is the most well studied, in particular with the pathogenesis and progression of IBD via triggering an altered immune responses to commensal microflora [12]. This response is associated with an array of cytokine upregulation as well as alteration in pyroptosis (programmed inflammatory cell rupture) thereby compromising the innate immune defense. Similarly inflammasome dysregulation, in particular for NLRP3 and NLRP6 have had adverse effects on progression of NAFLD, alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis B and C, hepatic fibrosis, nanoparticle induced injury and neoplastic disease [13].

High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) can be found in almost all sweetened, pasteurized, and processed foods, as it is cheaper and sweeter than cane sugar. It has been implicated in the growing epidemic of obesity, diabetes and metabolic syndrome. This has led some states to place restrictions on the sale of items containing HFCS, such as the number of large-volume sodas that can be purchased at any one time. Of note is that in 2012, the FDA turned down a petition from the corn producer industry to change the name of HFCS to “corn sugar” (https://www.sugar.org/resources/releases/fda-denies-petition-to-rename-high-fructose-corn-syrup/). Due to its primary hepatic metabolism and based on recent studies associating the development of NAFLD from overconsumption, a recent report suggested HFCS ingest ion should be considered a “public health crisis ” [14]. Additionally, a study where mice had a significantly greater increased colon tumorigenesis, in the absence of obesity or metabolic syndrome [15].

In my opinion, clinicians generally do a poor job of dietary recommendations outside of what we traditionally recognize for celiac, eosinophilic esophagitis and perhaps, irritable bowel. Although we may tell our NAFLD patients to “lose weight”, our IBD patients to “eat healthy” but what specifics and justifying rational do we provide, much less navigation tools to optimize compliance?

Although much of the cited evidence mentioned is animal based research, I believe there a translational message which is actionable now I suggest that clinicians take a proactive role moving patient diets toward plant-based foods, healthy fats (from butter to olive or canola oil), using herbs for flavor instead of salt, and lean protein with restriction of red meat (less than once/week)- basically promoting the “Mediterranean diet”. Additionally, we need to educate our patients to restrict and when possible, avoid processed foods and ingestion of HFCS. I suggest to my patients to “build up their meals” from healthy basic components, rather than “consume down” processed foods. Additionally, to read labels of foods they choose, being more attuned to the additive components.

It is time for us to start taking a proactive role addressing diet with our patients. Recognizably for some patient profiles, these recommendations may have more of an effect (exmaple: data with ’s comprehensive approach addressing each of the aforementioned topics has not been done. Avoidance of HFCS clearly is warranted in our patients with liver disease- in particular NAFLD. So if you do not discuss diet with your GI patients, recognize what may be left behind on the “therapeutic table”….!

Clinical Gastroenterology Journal received 33 citations as per Google Scholar report