Review Article - (2024) Volume 12, Issue 4

Received: 04-Oct-2021, Manuscript No. IJEMS-24-144559;

Editor assigned: 07-Oct-2021, Pre QC No. IJEMS-24-144559 (PQ);

Reviewed: 21-Oct-2021, QC No. IJEMS-24-144559;

Revised: 15-Jul-2024, Manuscript No. IJEMS-24-144559 (R);

Published:

12-Aug-2024

, DOI: 10.37421/2162-6359.2024.13.739

Citation: Soltani,Hassen, Ghandri Mohamed. "The

Impact of the Quality of Governance on Foreign Direct

Investment and Economic Growth: The Case of MENA Countries." Int J

Econ Manag Sci 13 (2024): 739.

Copyright: © 2024 Soltani H, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the creative commons attribution license which permits unrestricted

use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Using the dynamic GMM method from a sample of 15 MENA countries during the period 2000-2017, we tried to examine the impact of governance quality on FDI and economic growth in these countries. The results show that, in general, governance variables are positively correlated with economic growth, since the quality of the institutional infrastructure is very important for the attractiveness of FDI and the promotion of a country's growth. Similarly, FDI is significant and positively related to economic growth.

Foreign direct investment • Governance • Economic growth • GMM dynamic

The world from the beginning of the 90’s and with globalization, deregulation and technical progress, considerable changes affecting different economic sectors in different countries of the world, most of which have chosen an extroverted economic policy based on an extroverted industry to be able to improve its growth and economic development and to face the challenges of this openness while providing a suitable ground for global competition to attract more foreign investment.

As a result, the subject of attractiveness of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is still a subject of continuous interest for both countries of origin and host countries, since there is almost unanimous agreement on the advantages they can be leveraged through FDI, since they would create jobs, promote growth and economic development, enable knowledge and technology transfers and spur reform, especially for host countries.

This brings us back to studying the determinants of FDI and their potential effects on economic growth, since this is why governments of host countries take the necessary decision through their political actions. What brings us back today to talk about the notion of "good governance" which has been the subject of several research and studies in different fields and which must be based on a break with traditional politics and a democratization of the decision-making process based on the interdependence of powers related to collective action [1].

After presenting the various theoretical and empirical studies that have dealt with the triangular relationship between governance, FDI and economic growth, we will present our econometric model, our database, the results and the resulting interpretations.

Theoretical framework

To grasp the theoretical impact of FDI and economic growth, one must certainly go through the modern theory of growth that has its origins in the contributions of Solow and in neoclassical growth models where capital and are the only factors of production and always emphasize the accumulation of capital as a factor of growth.

According to Alaya, the main drawback of this model lies in the assumption of decreasing return on capital "which means that output growth may not be attributable to input growth". In other words, in the long term we cannot have growth unless we take into consideration innovation-related technologies linked to the progress of qualifications. This new factor, which is technical progress and which is considered as an exogenous factor of the model, has led specialists to develop other models in which the determinants of growth are endogenous, hence the pairing of the new growth theory [2].

Among the famous economists of the new theory of growth or the theory of endogenous growth in cities; Romer, Lucas, Barro and Sala-i-Martin and Grossman and Helpman. This theory emphasizes science and technology, human capital and the externalities of knowledge to sustain the economy and achieve sustainable growth in the long run. This theory differs from early post Keynesian growth models of savings and investment and neoclassical models of technical progress. This new theory was coincided with a rising trend towards globalization and integration into the global economy, so FDI and exports played an important role in this process.

Theoretically, there are generally two points of view on the impact of corruption on growth. Several authors stress the possibility that economic growth and/or development are negatively influenced by corruption. According to North, dishonest bureaucracies could delay the distribution of permits and licenses, thus slowing down the process by which technological advances fit into new equipment or production procedures. In addition, Shleifer and Vishney see that the bureaucrats can poorly guide investments towards projects offering better opportunities for corruption, such as defense and infrastructure [3].

Romer, suggests that corruption is a tax that prevents the entry of new products or technologies that require a fixed initial investment. An increase in corruption equates to a rise in taxes thus pulling talented entrepreneurs into the rent seeking sector, which lowers the rate of growth. In the same context, Murphy, et al., provide evidence about countries, where people talented are assigned to the annuity research activity, tend to grow more slowly [4].

However, there is a second part of the literature that suggests that corruption can really improve efficiency and help growth, particularly in the context of pervasive and burdensome regulation in developing countries. Several authors such as Leff, Huntington, Lui, suggest that corruption influences economic growth through two types of mechanisms: Corrupt practices such as "speed money" that would allow individuals to avoid bureaucratic delays and government employees who are allowed to collect "bribes" are then encouraged to work harder and more effectively. Although the first mechanism increases the likelihood that corruption is beneficial to growth only in countries with heavy bureaucratic regulations, the second mechanism is independent of bureaucratic procedures [5].

Empirical review

Through an analysis of panel data on 12 Latin American countries between 1950-1985, De Gregorio, finds a significant and positive relationship between FDI and economic growth. Similarly, he pointed out that the effect of FDI is more important than that of domestic investment and that FDI is more conducive to economic growth when the level of education in the host country is high [6].

Ilan Noy and Abdul Khaliq, used detailed sectoral data on FDI inflows over the period 1997-2006 to study the impact of FDI on growth in Indonesia. The results show that, in general, FDI has a positive effect on economic growth, but if the average growth performance in all sectors is taken into account, the positive effects of FDI are no longer apparent.

Sjoerd Beuglesdijk, et al., have attempted to study the impact of vertical and horizontal FDI on the growth of 44 host countries over the period 1983-2003 using traditional FDI figures as a benchmark. They found that there is a higher growth effect of the horizontal FDI (market seeking) on the vertical FDI (efficiency seeking) [7].

For Koupko, human capital and openness are the most important determinants of FDI to ensure good growth for UEMOA countries following a panel data study for the period 1996-2003.

In order to determine the direction of the relationship between FDI and growth, Zhang, conducted a study in 11 countries in Asia and Latin America. He has shown that there is no relationship between FDI and growth in Argentina in the short and long run, while in Brazil and Colombia there is an inverse relationship of growth to FDI. The author also finds a short-term relationship of growth to FDI in Korea, Malaysia and Thailand. Among 11 countries to study in only 5 countries growth is accelerated by FDI for the rest there is no co-integration relationship between FDI and growth.

According to an empirical demonstration, Brewer, has shown that there is a negative correlation between economic growth and FDI. Indeed, this negative correlation can be explained by the effect of the domination exercised by foreign firms on local firms which discourages them to develop their own research and development activities [8].

De Gregorio, Lee and Borensztein, have shown from a panel data study of 69 developing countries that a one percentage point increase in the ratio of FDI to GDP increases the poverty rate per capita GDP growth in the host country of 0.8%. Faouzi B, showed from a sample of 28 emerging countries over a period from 1984-2002, there is a strong correlation between country risk indicators and FDI [9].

From an econometric study of dynamic panel data on 7 WAEMU countries over the period 1972-2002, Batana YM, showed that the domestic investment rate, public consumption and the previous FDI are the most relevant factors in explaining FDI flows in UEMOA countries [10].

In other studies, that use more specific measures of governance Hellman, Jones and Kaufman, find that corruption reduces FDI inflows for a sample of countries in transition. For Carstensen and Toubal, they used a macroeconomic risk ranking found in "Euro money" to estimate a panel data model on the determinants of FDI in central and eastern European countries. The country least risky in the ranking of "Euro money" is the most attractive country in terms of FDI [11].

In a more recent study, Soltani Hassen and Ochi Anis, supported a traditional time series model of annual data covering the period from 1976 to 2009 for Tunisia. The results from the model suggest that the effect of FDI is significantly positive on a few driving variables of economic growth, namely human capital and financial development [12].

Data and methodology

In this paper we will try to empirically study and evaluate the triangular relationship between governance, FDI and economic growth in 17 MENA countries (Egypt, Tunisia, Algeria, Jordan, Jordan, Morocco, Libya, Lebanon, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Israel and Iran) over a period from 2000 to 2017.

We will use the GMM method (the method of moments generalized) dynamic panel, our database is extracted from the world bank; world development indicators and worldwide governance indicators (the world bank group) [13].

Model specification

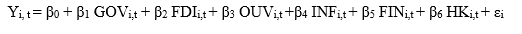

The growth equation we are going to estimate is the one used in the work of Sami N. and Samir G and is as follows:

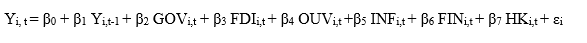

To avoid the problem of endogeneity of the variables and to control the individual and temporal specific effects, it seems to us that the use of the Arellano and Bond, estimator of taking for each period the first difference of the equation to be estimated is relevant for eliminating country specific effects and for instrumenting lagged explanatory variables. The delayed variable in our model is "Y" so the model will be rewritten as follows:

Description of variables

• Yi, t : Per capita real GDP growth rate

• Yi, t-1: Real GDP growth rate per capita delayed

• GOVi,t: The different governance variables (the fight against

corruption (CORR), the rule of law (STATE), political stability

and absence o f v iolence (STAB), voic e and responsibility

(VRES), the quality of regulation (QUAL) and government

effectiveness (EFI)

• FDIi,t: Foreign direct investment net inflows as % of GDP

• OUVi,t: Rate of opening measured by the t otal of X° and M°

relative to GDP

• INFi,t: Inflation rate

• FIN: Financial develo pm e nt meas ur es t h e o f degree

development of the financial sector (Money and quasi money

(M2) as a % of GDP)

• HKi,t: Human c apital measured by th e secondary school

enrollment rate

The result of the estimation of the growth function by the dynamic GMM panel method with STATA 11.0 software is shown in the table below (Table 1).

| Variables | Coefficient | Std, Err | z | P>|Z| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yi, t | ||||

| L1 | 0.1847876 | 0.0724626 | 2.55 | 0.011 |

| VRES | 0.0074746 | 0.0176206 | 0.42 | 0.671 |

| STAB | 0.0187861 | 0.0394469 | 0.48 | 0.634 |

| EFI | 0.0003917 | 0.0607402 | 0.01 | 0.995 |

| QUAL | -0.00022 | 0.0045187 | -0.05 | 0.961 |

| ETAT | 0.1051164 | 0.0676738 | 1.55 | 0.120 |

| CORR | 0.0039919 | 0.0436518 | 0.09 | 0.927 |

| FDI | 0.151709 | 0.1120134 | 1.35 | 0.176 |

| OUV | 0.0065616 | 0.0281663 | 0.23 | 0.816 |

| INF | -0.0491545 | 0.0464807 | 1.06 | 0.290 |

| FIN | 0.0031622 | 0.0296033 | 2.11 | 0.915 |

| HK | -0.0095646 | 0.0408053 | -0.23 | 0.815 |

| CONS | -5.371562 | 5.987778 | -0.90 | 0.370 |

| Wald chi2 (13) Prob>chi2 Nb of instruments | 16.92 | 0.2031 | ||

Note: Instruments for differenced equation GMM-type: L(2/.).Y

Standard: D.vres D.stab D.efi D.qual D.etat D.corr D.ide D.ouv D.inf D. fin D.hk D.fbcf, Instruments for level equation Standard: _cons

Table 1: The estimation of the growth function by the dynamic GMM panel method.

In general, the table notes that there are variables that are statistically significant and others that are not and that may be positively or negatively correlated with the dependent variable.

According to our result, the variable (Yi,t-1) is significantly positive, which means that the growth rate of the real GDP per capita of the year (t) depends positively on that of the year (t-1).

For governance variables, they are overall insignificant and positive with the dependent variable except for the government quality variable (QUAL) which is negatively related to the variable (Yt). This may reflect the government's inability to provide and put in place policies and regulations that promote economic development [14].

For FDI, this variable is significant and positively correlated with economic growth; as long as there is incoming FDI as long as there is an improvement in the country's economic growth. This result may explain the continued interest of most countries in the MENA region in attracting more FDI that can be an alternative source for financing their economic activity given the weakness of their national savings and the heavy debt load [15].

For the trade opening control variable (OUV) that is positively insignificant, its effect is dependent on the estimation method and the variables that are included in the estimate. Zagha, et al., have argued that trade reforms depend on country specific conditions and how the liberalization process is implemented, for these authors trade opening is an opportunity and not a guarantee and it is naïve to think that the simple opening of an economy or the reduction of tariffs leads directly and automatically to economic growth [16].

Inflation (INF) is significant and negatively correlated with economic growth, which confirms the idea of Romer C and Romer D, that inflation has deleterious effects on economic growth. The financial development variable (FIN) is positively correlated with the dependent variable (Yt), the more a country has a fairly developed financial system the more it tends to attract more FDI and therefore to promote its economic growth since this variable is a measure type of financial depth and therefore the overall size of financial intermediation [17].

Finally, the variable human capital (HK) is negatively correlated with economic growth, this result is contradictory with some theoretical and empirical work such as those of Borensztein et al., Makki and Somwaru. But in some studies the variable (HK) does not capture the actual level of human capital development, for example, Bashir, reports a negative correlation between human capital and growth in a study done in a number of countries MENA region similarly Nyatepe Coo, from a study of a number of developing countries to find a significant negative correlation between (KH) and economic growth. For some economists, the difference in results may be due to the lack of a consensus on which is the best indicator that measures the level of human capital [18].

In this paper we have tried to examine the dynamic relationship between the institutional environment, FDI and economic growth. We used a sample of 17 MENA countries during the period 2000-2017 using the dynamic panel Generalized Moments (GMM) Method.

The results indicate that over the period studied, FDI and institutional infrastructure were the two most important determinants of economic growth. Similarly, the results show that the impact of FDI on economic growth has been driven more by efficiency than by increased domestic investment, prompting MENA countries to focus on policies that promote institutional development to become an attractive destination for FDI.

In the same context, these countries need to know how to direct FDI flows to sectors that offer increasing returns to domestic investment and production. Countries in the MENA region need not only focus on the amount of inward FDI but how it will be used to promote growth and reduce poverty and income inequality between regions.

The authors are thankful to the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at University of Bisha for supporting this work through the Fast-Track Research Support Program.